WATER AUDIT CALIFORNIA

A PUBLIC BENEFIT CORPORATION

952 SCHOOL STREET #316 NAPA CA 94559

VOICE: (707) 681-5111

EMAIL: LEGAL@WATERAUDITCA.ORG

June 1, 2023

Napa County Board of Supervisors 1195 Third Street, Ste. 310

Napa, CA 94559

APPEAL PACKET – ADDITIONAL SHEETS

(Appellant Water Audit California)

Appealing Duckhorn Vineyards Winery – May 3, 2023, decision of the Napa County Planning Commission’s adoption of the Mitigated Negative Declaration and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program, and approval of Use Permit Major Modification Application P19-00097-MOD

Appellant Name and Contact Information:

Water Audit California

952 School Street, PMB 316

Napa, California 94559

Legal@WaterAuditCA.org 530-575-5335

Grounds for Appeal

Water Audit California (“Water Audit”) hereby appeals the May 3, 2023, decision of the Napa County Planning Commission’s adoption of the Mitigated Negative Declaration (“MND”) and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program (“MMRP”) and approval of Use Permit Major Modification Application P19-00097-MOD (collectively the “Application”), as captioned above.

Water Audit appeals on its own behalf, on behalf of the general public and in the public interest. Water Audit has standing to appeal based on the submission of comment and testimony during the May 3, 2023 hearing. (see Napa County Code sec. 2.88.010 (G).)

Water Audit asserts that there was not a fair and impartial hearing. Critical issues were not considered, and evidence was withheld or misrepresented as discussed below.

There was no inquiry into potential injury to the public trust. Critical findings underlying the MND are not supported by the evidence. There is long term and extensive evidence of existing environmental injury; the projected water demand for the project is greater than the groundwater recharge from the site; and the proposed project will consume more water than the existing facility.

As separate and additional grounds for reversal of the Application, it is submitted that the proposed sole source of potable water has not been approved or reviewed by Department of Health or Division of Drinking Water and the City of St. Helena has not reviewed or commented on the project, and therefore there has not been a full and complete review of the project as required by the California Environmental Quality Act (“CEQA”). It is further submitted that the adopted Recommended Findings (Use Permit Major Modification Application Attachment (“Attachment”) A – Recommended Findings (“Findings”) have failed to include a mandatory term of mitigation required by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (“CDFW”) and therefore the project poses a potential adverse effect on wildlife resources. Finally, to the extent that the project seeks to rely upon the importation of grapes, it does not comply with the terms of the Agricultural Land Preserve or the Williamson Act.

Introduction

Water Audit is a public benefit organization dedicated to advocating for the public trust. Our interest in this matter is greater than the decision regarding this project alone. This matter, and the existing environmental condition, are representative consequences of the failure of Napa County to perform its duties to protect the public trust.

The essential idea of the public trust doctrine is that the government holds and protects certain natural resources in trust for the public benefit. (See Illinois Central Railroad v. Illinois (1892) 146 U.S. 387, 452, 456; National Audubon Society v. Superior Court (1983) 33 Cal.3d

419, 441; Berkeley v. Superior Court (1980) 26 Cal.3d 515, 521.)

Public trust theory has its roots in the Roman and common law (United States v. 11.037 Acres of Land (N.D. Cal. 1988) 685 F. Supp. 214, 215.) and its principles underlie the entirety of the State of California. Upon its admission to the United States in 1850, California received the title to its tidelands, submerged lands, and lands underlying inland navigable waters as trustee for the benefit of the public. (People v. California Fish Co. (California Fish) (1913) 166 Cal. 576,

584; Carstens v. California Coastal Com. (1986) 182 Cal.App.3d 277, 288.) The People of California did not surrender their public trust rights; the state holds land in its sovereign capacity in trust for public purposes. (California Fish, Ibid.)

The courts have ruled that the public trust doctrine requires the state to administer, as a trustee, all public trust resources for current and future generations, specifically including the public trust in surface waters and the life that inhibits our watercourses. These trust duties preclude the state from alienating those resources into private ownership, and requires the state to protect the long-term preservation of those resources for the public benefit. (National Audubon, supra. 33 Cal.3d 419, 440-441; Surfrider Foundation v. Martins Beach 1, LLC (2017) 14 Cal.App.5th 238, 249-251; Public Resources Code § 6009.1.) The public trust fulfills the basic elements of a trust: intent, purpose, and subject matter. (Estate of Gaines (1940) 15 Cal.2d 255, 266.) It has both beneficiaries, the people of the state, and trustees, the agencies of the state entrusted with public trust duties.

The beneficiaries of the public trust are the people of California, and it is to them that the trustee owes fiduciary duties. As Napa County is a legal subdivision of the state, it must deal with the trust property for the beneficiary’s benefit. No trustee can properly act for only some of the beneficiaries – the trustee must represent them all, taking into account any differing interests of the beneficiaries, or the trustee cannot properly represent any of them. (Bowles v. Superior Court (1955) 44 C2d 574.) This principle is in accord with the equal protection provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution.

A public trust trustee “may not approve of destructive activities without giving due regard to the preservation of those [public trust] resources.” (Center for Biological Diversity, Inc. v. FPL Group, Inc. (“Bio Diversity”) (2008) 166 Cal.App.4th 1349, 1370, fn. 19, 83 Cal.Rptr.3d 588.) [Emphasis added]

Common law imposes public trust considerations upon the County’s decisions and actions pertaining to trust assets. (Biological Diversity, supra. 166 Cal.App.4th 1349; Environmental Law Foundation v. State Water Resources Control Board (“ELF”) (Cal. Ct. App. 2018) 26 Cal.App.5th 844.) The courts have recognized the State’s responsibility to protect public trust uses whenever feasible. (See, e.g., National Audubon, supra. 33 Cal.3d 419, 435; California Trout, Inc. v. State Water Resources Control Bd. (1989) 207 Cal.App.3d 585, 631; California Trout, Inc. v. Superior Court (1990) 218 Cal.App.3d 187, 289.) Napa County, under Public Resources Code, section 6009.1, has an affirmative duty to administer the natural resources held by public trust solely in the interest of the people of California.

The public trust doctrine requires Napa County, as a trustee, to manage its public trust resources (including water) so as to derive the maximum benefit for its citizenry. Even if the water at issue has been put to beneficial use, it can be taken from one user in favor of another need or use. The public trust doctrine holds that no water rights in California are truly “vested” in the traditional sense of property rights.

There can be no vested rights in water use that harm the public trust. Regardless of the nature of the water right in question, no water user in the State “owns” any water. Instead, a right to water grants the holder thereof only the right to use water, an “usufructuary right”. The owner of “legal title” to all water is the State in its capacity as a trustee for the benefit of the public. All water rights are usufructuary only and confer no right of private ownership in the water or the watercourse, which belongs to the State. (People v. Shirokow (1980) 26 Cal.3d 301 at 307.)

The Standard for Review

There is more than a fair argument that injury could occur as a result of the proposed Duckhorn project and that a full Environmental Impact Report (EIR) is one of the likely remedies. “The foremost principle under CEQA is that the Legislature intended the Act to be interpreted in such manner as to afford the fullest possible protection to the environment within the reasonable scope of the statutory language.” (Sierra Club v. County of Fresno (2018) 6 Cal.5th 502, 511.)

In describing the scope of judicial review of an agency’s application of the fair argument standard, the Supreme Court has stated: “If there [is] substantial evidence that the proposed project might have a significant environmental impact, evidence to the contrary is not sufficient to support a decision to dispense with preparation of an EIR and adopt a negative declaration, because it [can] be “fairly argued” that the project might have a significant environmental impact. Stated another way, if the [reviewing] court perceives substantial evidence that the project might have such an impact, but the agency failed to secure preparation of the required EIR, the agency’s action is to be set aside because the agency abused its discretion by failing to proceed “in a manner required by law.’ ” ” (Citation omitted.) “The fair argument standard thus creates a low threshold for requiring an EIR, reflecting the legislative preference for resolving doubts in favor of environmental review. [Citation.]” Save the Agoura Cornell Knoll v. City of Agoura Hills (2020) 46 Cal.App.5th 665, 675-7 (Emphasis added)

1. A “Finding” requires a hearing that considers evidence. Critical Findings underlying the MND are not supported by the evidence.

A planning commission hearing is quasi-judicial in nature. A commission has a duty to hear and weigh evidence and make a finding of facts (“Finding”) at the conclusion of its deliberations.

Although such boards do not have the character of an ordinary court of law or equity, they frequently are required to exercise judicial functions in the course of the duties enjoined upon them. In Robinson v. Board of Suprs. (1979) 16 Cal. 208 the court says: ‘It is sufficient if they are invested by the legislature with power to decide on the property or rights of the citizen. In making their decision they act judicially whatever may be their public character. (Nider v. Homan (1939) 32 Cal. App. 2d 11, 16.)

Through Government Code, section 65800 et seq., the Legislature conveyed to the County the authority to adopt regulations and ordinances to promote the general welfare of the State’s residents by control over zoning matters. Government Code, section 65101 states in part: “The legislative body [i.e. the Board of Supervisors] may create one or more planning commissions each of which shall report directly to the legislative body.” The Napa County Planning Commission performs the function of a planning agency.

Notwithstanding the State’s sweeping assignment of powers, the County remains subordinate to the control and direction of the senior levels of government. Specifically, Napa Ordinances Title 18 requires that the County’s actions conform to state law. Courts have held that substantial evidence must support the award of a variance in order to ensure that legislative requirements have been satisfied. (See Siller v. Board of Supervisors (1962) 58 Cal.2d 479, 482; Bradbeer v. England (1951) 104 Cal.App.2d 704, 707.) To be admissible, evidence must be relevant, material, and competent. Evidence is considered “competent” if it complies with certain traditional notions of reliability. To be admissible and competent, evidence must be present.

In 2005 the Napa Department of Public Works, Division of Environmental Health published a memorandum regarding Use Permits and Regulated Water Systems (“2005 Regulated Water System Memo”) and the required Technical, Managerial, and Financial Capacity Worksheet (“Worksheet”) for Planning staff review of non-community water systems. The Worksheet was subsequently revised in 2018.

The purpose of this memo is to provide information regarding requirements for regulated water system permitting. The Division of Environmental Health has a contract with the California State Water Resources Control Board (Water Board) to administer the small water system program. Public water systems are required to be permitted by Water Board or the local delegated agency.

The Worksheet provides a water availability analysis shall be done for a ten-year period; the Bartelt WAA projected for only one year. (Attachment H – Water Availability Analysis_Tier 1) The Worksheet calls for examination of existing well logs. The Bartelt WAA did not discuss the topic, relying solely on statistical norms. (see Id.) The Worksheet calls for groundwater logs.

Although the Bartelt WAA asserted that reference had been made to such logs, they are not part of the Application or the public record. (see Id.) Duckhorn avowed that it has been submitting extraction records to Napa County, (see proceedings from Planning Commission May 3, 2023 Hearing.) but no records were available to Water Audit’s public records request.

More importantly, the Worksheet calls for a characterization of the water quality. Bartelt wrote: “Water quality results were not available for the irrigation wells prior to completion of this WAA. Water quality results for the ‘Domestic Well #1’ that provides water to the NTNCWS were not reviewed because it is assumed the water system complies with all Federal, State, and local laws governing public water systems.” (Attachment H, p. 5.)

The Bartelt WAA states that “Annual Consumer Confidence Reports (CCR) have been submitted to the State and/or County…” (Attachment H, p. 5.) That statement is not true. In fact, not once in the last six years has a fully conforming CCR been filed. In 2017, 2018, 2019 and 2022 no reports were filed. In 2020 and 2021 reports were filed but not certified. (see Exhibit 1.)

The Worksheet requires planning staff to evaluate “the feasibility of consolidation with other (existing) systems. The Bartelt WAA again does not address the topic (see Attachment H). This Worksheet was referenced in the Bartelt WAA, but not submitted for public or planning commission review, “Refer to the Technical, Managerial, and Financial (TMF) Capacity worksheet for additional information on the existing public water system (PWS) and proposed modifications included with the Use Permit Modification Application.” (see Attachment H, p. 3) Water Audit only obtained a copy of the Technical, Managerial, Financial (“TMF”) Capacity Worksheet document in response to a Public Records request. The TMF is dated 2019, and addresses the subject by stating:

The closest large-scale municipal water system is operated by the City of Saint Helena. This municipal water system is not located within the vicinity of the proposed water system for the Duckhorn Vineyards Winery project. It is infeasible to consolidate with any existing water systems at this time. If municipal water service becomes available in the future, it is anticipated that the onsite well will continue to be utilized for wine production and any municipal water service would be utilized for domestic purposes. There is no anticipated consolidation with other (existing) water systems near the site. (TMF, p. 4.)

In fact, the recently approved use permit from applicant Freemark Abbey project “Inn at the Abbey” is located at the other end of Lodi Lane and has a connection to City of St. Helena water. (See Exhibit 2.) It was an abuse of discretion not to discuss this alternative. See City of St. Helena following.

According to Attachment H, at p.2:

“[a} Tier 2 well interference analysis need only be conducted when ‘substantial evidence in the record indicates the need to do so under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).’1 2 At the request of Napa County Planning, Building, and Environmental Services Division, a Tier 2 and Tier 3 Water Availability Analysis was prepared by Wagner & Bonsignore and has subsequently been submitted to Napa County.” (emphasis added)

The Applicant directly states in the record that “[t]he DVW project team has conducted extensive analyses of anticipated groundwater usage and potential effects on adjacent wells and the Napa River. Specifically, in addition to the standard Tier 1 Water Availability Analysis, Tier 2 & 3 analyses have been conducted as outlined in the County of Napa Water Availability Analysis Guidelines (May 2015) … The complete Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 analyses are included as part of the documents submitted in support of the Modification application.” (Attachment D – Use Permit Major Modification Application, p. 6.)

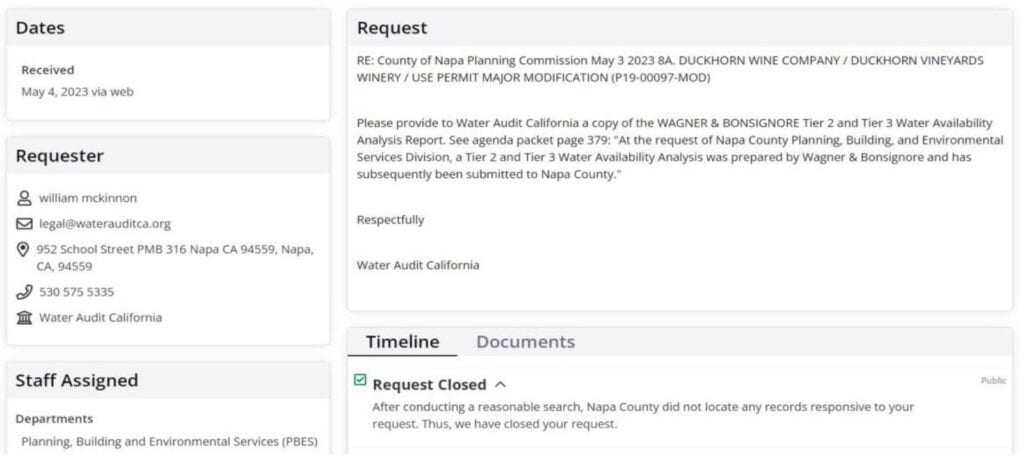

Subsequent to the May 3, 2023 hearing, Water Audit submitted a Public Record Act request to Napa County on May 4, 2023, which stated “Please provide to Water Audit California a copy of the WAGNER & BONSIGNORE Tier 2 and Tier 3 Water Availability Analysis Report. See agenda packet page 379: ‘At the request of Napa County Planning, Building, and Environmental Services Division, a Tier 2 and Tier 3 Water Availability Analysis was prepared by Wagner & Bonsignore and has subsequently been submitted to Napa County.’”

On May 24, 2023, the County responded “After conducting a reasonable search, Napa County did not locate any records responsive to your request. Thus, we have closed your request.”

In spite of the above representations of Duckhorn and Bartelt, a Tier 2 or Tier 3 Analysis was not a part of the record that was considered by the Commission on May 3, 2023, nor is it available as a public record. Therefore, the Commission erred when it approved the Application as it relied on statements, presented as facts, when evidence supporting those statements is not a part of the record. Thus, the record does not meet basic evidentiary rule requirements as a part of regulated decision making.

2. The MND fails to consider substantial evidence of existing environmental injury.

In rejecting the need for a Tier 2 and Tier 3 analysis, the Planning Department spokesperson opined that it was not necessary under Water Availability Analysis Guidelines (“WAA 2015”) as there was no evidence of existing environmental injury. (see proceedings from Planning Commission May 3, 2023 Hearing.) The Application and Napa County did not present or discuss any of the extensive study data that shows injury to the public trust that has been assembled over nearly thirty years.

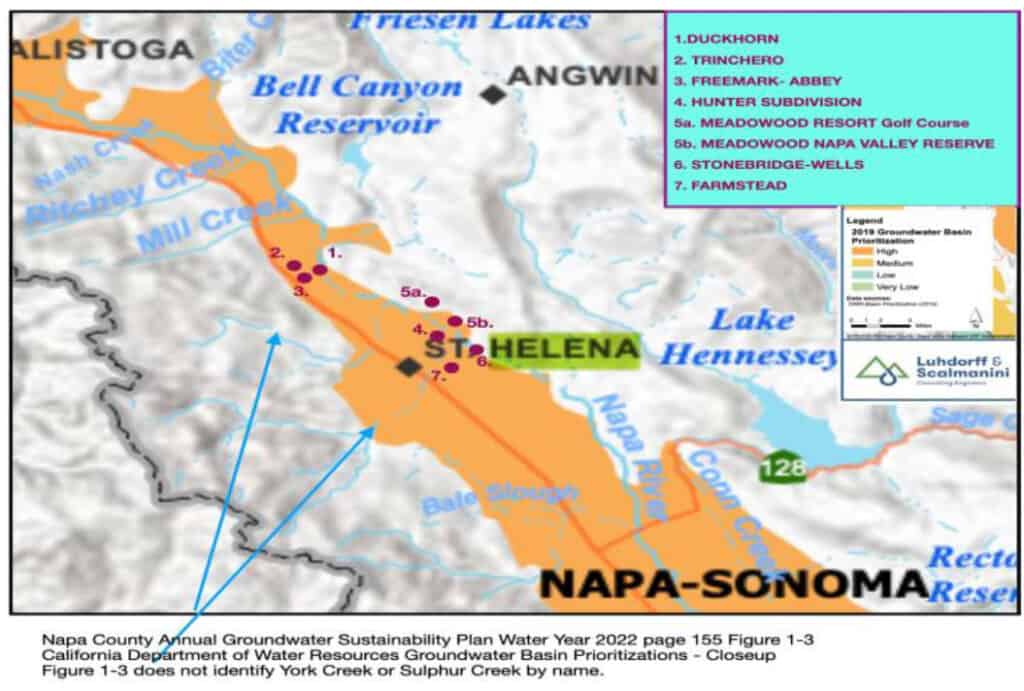

The relationship between groundwater extraction and Napa River flows was reported in November 1994 when the City of St. Helena (CSH) commissioned a report from Richard C. Slade and Associates titled Hydrological Assessment for Water Well Feasibility for City of St. Helena,

Napa Valley, California (“Hydrological Assessment”). It considered the conditions proximate to Pope Street and the Napa River, approximately two miles downstream from Duckhorn. Similar geological conditions exist in both locations.

The Hydrological Assessment presented information and conclusions that indicate a hydrologic connection between the groundwater system and surface water contained in the Napa River. It concluded that there is a surface water/groundwater interface by which the Napa River recharges the groundwater system pumped by production wells, even if the wells are screened only in the deeper volcanic rocks. It reports that production wells screened and/or gravel packed in the alluvium can nevertheless draw directly from the alluvium that is in direct contact with the Napa River.

Over a decade ago, the County’s consulting engineers, Luhdorff and Scalmanini Consulting Engineers (LSCE) informed a citizen’s advisory committee of the diminution of surface flows by groundwater extraction. In its April 2014 final report to the Board of Supervisors the Groundwater Resources Advisory Committee (GRAC) recognized the potential problem of extractions dewatering surface waters and voted to ignore the issue. The majority of GRAC members recommended the County maintain the existing WAA [water availability analysis] process, not revise the well-to-well interference criterion, and not add a new criterion for well-to- surface water interference.

In September 2014, the Legislature adopted the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA); Wat. Code, section 10720 et seq. The valley portion of Napa County was identified as a priority sub-basin. Duckhorn is within the defined sub-basin. SGMA required Napa County to either submit evidence by the end of 2017 that the County was sustainable in its groundwater utilization (herein an “Alt Plan”), or form a groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) to develop and implement a groundwater sustainability plan (GSP) to avoid undesirable results and mitigate overdraft.3

In 2015, Napa County adopted Water Availability Analysis Guidelines (WAA 2015). While the WAA provided for review of larger wells that were proposed to be located proximate to watercourses, the provisions were not vigorously enforced. Water Audit frequently reviewed applications where blue water streams and water courses have been simply left off submittals; their omission unnoted by staff.

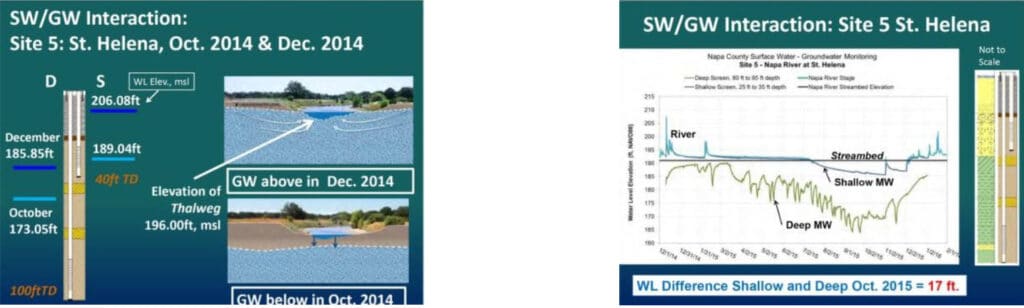

Also in 2015, LSCE reported to the Napa County Watershed Information and Conservation Council (“WIIC”) an example site of the dewatering surface waters by groundwater extraction earlier report to the GRAC: the cause of the Napa River drying at Pope Street in St. Helena. In two slides, LSCE showed the relationship between groundwater extraction, a lower groundwater level, and a dry river. The site presented is approximately two miles downstream of the project, and has similar hydrogeological characteristics.

In 2016, LSCE recommended that Napa County install additional monitoring of groundwater/surface water interactions in areas where data was lacking. No additional monitoring was installed.

In 2017, Napa County submitted an Alt Plan that claimed stable groundwater levels over a 28-year base period. In the Alt Plan LSCE avoided discussing substantively the issue of potential injury to the public trust or interference with groundwater dependent ecosystems (GDE). Under SGMA, GDEs are ecological communities or species that depend on groundwater emerging from aquifers or groundwater occurring near the ground surface (GSP Regulation, section 351, subdv. (m)).

The Alt Plan was rejected by the Department of Water Resources (“DWR”) in November 2019. As the DWR Rejection (“Rejection”) largely mirrors current difficulties, the agency’s comments are recited at length.

The DWR stated that the County’s sustainability indicators section conflated “three requirements of the sustainable management criteria set out in the GSP Regulations: undesirable results, [UR] minimum thresholds, [MT] and measurable objectives [MO].” For clarity they were explained by the DWR as follows:

- 23 CCR 354.28(c)(1) specifies that the MT for chronic lowering of groundwater levels shall be based on groundwater elevations indicating a depletion of supply that may lead to undesirable results;

- 23 CCR § 354.28(c)(2) specifies that the minimum threshold for depletions of interconnected surface water shall be the rate or volume of surface water depletions caused by groundwater use that has adverse impacts on beneficial uses of the surface water and may lead to undesirable results; and

- 23 CCR § 354.32 requires that each basin be monitored, and that a monitoring network include monitoring objectives, monitoring protocols, and data reporting requirements be developed that shall promote the collection of data of sufficient quality, frequency, and distribution to characterize groundwater and related surface water conditions in the basin and evaluate changing conditions.

The DWR Rejection noted that the sub-basin was inadequately monitored: only eight wells had ten years of reporting, and surface water ground water interfaces were inadequately measured. More importantly for the purposes of this appeal, the DWR reported the County established that there were diminished baseline flows that had to be taken into consideration.

Of the representative monitoring wells used for groundwater levels, storage, and depletions of interconnected surface water, 10 of the wells did not have 10 or more years of data. These 10 wells are the multi-completion wells installed in 2014, specifically for monitoring surface water-groundwater interactions. …

… the County proposes that historically diminished baseflow, although it could be considered an undesirable result, should not be disqualifying because SGMA does not require an agency to address undesirable results that occurred before, and have not been corrected by, January 1, 2015.

While it is true that SGMA does not require undesirable results prior to 2015 to be remediated, the presence of undesirable results before 2015 undermines the County’s claim that it has operated the Napa Valley Subbasin without undesirable results.

The DWR Rejection said in part: “The [Alt Plan] notes that the historical occurrence of diminished baseflow could be considered an undesirable result but claims that this possibility is basically immaterial inasmuch as SGMA does not require an alternative to address undesirable results that occurred before, and have not been corrected by, January 1, 2015.” This is the same existing injury argument that Napa County has used to decline to discuss Tier 2 and Tier 3 review of groundwater extraction.

The DWR response to Napa County is informative:

The County pivots on this point, taking language from SGMA and employing it to make two arguments. The County notes that a GSP is not required to address undesirable results that occurred before, and have not been corrected by, January 1, 2015, and that a groundwater sustainability agency has discretion to set measurable objectives and the timeframes for achieving any objectives for those undesirable results. The County applies both provisions to its situation. …

At any rate, the 2015 baseline for undesirable results is simply a limitation on what conditions must be addressed; it does not operate as an exoneration of the undesirable result itself. SGMA may not require a basin to reverse the effect of undesirable results to pre-SGMA conditions, but if undesirable results occurred during the 10-year period of the Alternative, that basin cannot demonstrate that it operated within its sustainable yield. (Emphasis added)

In early 2020, Water Audit wrote to the Napa Board of Supervisors urging them to consider public trust issues and highlighting portions of LSCE reports that indicated adverse surface water groundwater interface. The County was advised of its duty to the public trust. Caution and increased monitoring were recommended. A public Forum was held to deliver the message. The response from the County has been for the Director of Planning (current acting CEO) to repeatedly deny any responsibility for sufficient stream flows.

In 2022, a Napa County Groundwater Sustainability Plan (“GSP”) was prepared and filed that represented the Basin to be operated within sustainable limits and without GDE injury requiring remediation. Notice that the GSP was approved was received by Napa County in January 2023.

Because the drying of the Napa River at CSH predated 2015, the GSP continued to document the drying reach but no longer considered the drying reach a reportable injury under SGMA. (See GSP 6-50 and Figure 6-18. See also: Calculated Depth to Groundwater at Napa River Thalweg within One Mile of Monitored Wells, Spring 2010, Figure 121; Spring 2015; GSP Figure 6-122, Spring 2019, GSP Figure 6-123-a; Surface Water-Groundwater Hydrograph Site 5: Napa River at Pope Street, GSP Figure 6-18.)

Although a pre-2015 injury may not be remediated under SGMA, the courts have held that even long-standing injuries are subject to public trust review. (See Audubon, supra. 33 Cal.3d 419; California Trout, Inc. v. State Water Resources Control Bd. (1989) 207 Cal.App.3d 585 (Cal Trout I); California Trout, Inc. v. Superior Court (1990) 218 Cal.App.3d 187 (Cal Trout II); ELF, supra. 26 Cal.App.5th 844.)

In March 2023, LSCE authored a report entitled the Napa County Groundwater Sustainability Annual Report – Water Year 2022. (herein “LSCE 2023”) It states that from 2015 to 2022 the County monitored from 13 to 15 representative monitoring sites in proximity to CSH. (LSCE 2023, Table 6.3.)

Over pumping of groundwater impairs groundwater dependent ecosystems. (LSCE 2023, Figure 4-2.) The saturated thickness of the alluvial aquifer substantially increased in most parts of the Subbasin between Spring 2021 and Spring 2022 with a predominant range of one foot to 10 feet (LSCE 2023, Figure 6-21). Notable declines in saturated thicknesses (five to seven feet) occurred in some areas north of St. Helena, i.e. in the area of the Duckhorn project. (LSCE 2023, p. 74.)

LSCE 2023 contains the admission that, contrary to the representation of Napa County’s sustainable conduct in the GSP, groundwater extraction has exceeded sustainable limits in five of the last seven years.

The LSCE 2023 report states:

Groundwater pumping was a total of about 18,790 AF in WY [water year] 2022, exceeding the MT [minimum threshold] for reduction of groundwater storage. Additionally, groundwater pumping in WY 2022 results in 18,023 AF as the seven-year groundwater pumping average. The seven-year groundwater pumping average in WY 2022 qualifies as an undesirable result in the Subbasin. (Emphasis added)

The information is readily available to determine whether Duckhorn is causing or will cause injury to the public trust. Bartlet’s WAA states “At the request of Napa County Planning, Building, and Environmental Services Division, a Tier 2 and Tier 3 Water Availability Analysis was prepared by Wagner & Bonsignore and has subsequently been submitted to Napa County.” (Attachment H, p. 2.)

See also:

“The DVW project team has conducted extensive analyses of anticipated groundwater usage and potential effects on adjacent wells and the Napa River. Specifically, in addition to the standard Tier 1 Water Availability Analysis, Tier 2 & 3 analyses have been conducted as outlined in the County of Napa Water Availability Analysis Guidelines (May 2015). The report reaches the following conclusions:

- From review of the Tier 1 WAA analysis and discussions with Duckhorn Vineyards, the only well with a planned increase in pumping demand is Domestic Well #1, which will provide water supply for the new winery facilities. Of the four remaining onsite wells, Irrigation Wells #1 and #3 are planned for abandonment, Well #2 will have reduced pumping demand (from removal of vineyard and possible processed water use for irrigation), and Well #4 will have no change in annual demand.

- From the well logs, geologic maps and reports reviewed, and our analysis, groundwater pumping influence from onsite Domestic Well #1 and Well #4 under confined aquifer conditions, appears to have a potential to reach neighboring wells. However, our analysis indicates the effects would be relatively minor and within the default values given on Table F-1 of the County WAA Guidance Document.

- Review of the well completion report for Domestic Well #1 indicates that it draws water supply from tuffaceous units of the Sonoma Volcanics. The Napa River is incised into young alluvial deposits that extend to a depth of 40 feet and were sealed off from the volcanics during well construction. No direct connection to the overlying alluvium is indicated in the well log.

- Analysis of potential streamflow depletion using the USGS program STRMDEP08 indicates that pumping from the project well (Domestic Well #1) might have a small effect on the Napa River if some infiltration were to occur through a leaky However, the effects when pumping at the water system design output of 12 gpm appears to be very small and not likely measurable, if it is occurring.

The complete Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 analyses are included as part of the documents submitted in support of the Modification application.”

The DWR has stated that the reported depletions of interconnected surface water also have significant and unreasonable adverse impacts. LSCE 2023 reported an undesirable result when the representative monitoring site in the proximity of the Duckhorn project fell below the minimum threshold. (LSCE 2023.)

This withholding of evidence precludes the ability to challenge conclusions allegedly found on this data. For example, the assertion “No direct connection to the overlying alluvium is indicated in the well log” appears to be in direct contradiction to the conclusion in the Slade report that production wells screened and/or gravel packed in the alluvium can nevertheless draw directly from the alluvium that is in direct contact with the Napa River. This conflicting professional opinion can be resolved by qualified expert review of Tier 2 and Tier 3 analyses.

3. The Proposed Water Demand exceeds groundwater recharge.

On its face, the 14.0 acre-feet proposed water demand by Duckhorn is in excess of current limits. The current water use criteria for a parcel located within the “Napa Valley Floor” area is defined as 0.3 acre-feet per acre per year, or 9.7± acre-feet per year for the project.4

Water supply resiliency is a threshold of significance for land use change or development projects. This project requires an EIR that must first answer the question posed by CEQA, Section G, XVIII Utilities and Service Systems (d).: “Would the project have sufficient water supplies available to serve the project from existing entitlements and resources, or are new or expanded entitlements needed?”

The public trust imposes a second related question for its trustees: “Can existing uses

continue, or must they be abated to mitigate injury to the public trust?”

Although the winery has been in operation since 1976, no tangible evidence is disclosed in the Application of actual historical or present water use; the Application relies exclusively on statistical norms. “The groundwater demand generated … is estimated to remain the same.” (Attachment H, p. 7) “The total estimated water usage for the existing and proposed uses for the project is calculated based on the Guidelines for Estimating Residential and Non-residential Water Use.” (Attachment H, p. 5)

“When the well’s dry, we know the worth of water.” -Benjamin Franklin

4. The evidence shows the proposed project will consume more water than the existing facility.

The adopted Findings summarily state that water saving features would reduce the overall groundwater use of the project.

The project is considered not to have potential to significantly impact groundwater resources. Because the projected water demand for the project is below the estimated water availability acre feet per year for the parcel, the requested Use Permit is consistent with General Plan Goals CON-10 and CON-11, as well as the policies mentioned above that support reservation and sustainable use of groundwater for agricultural and related purposes. The project will not require a new water system or other improvements and will not have a negative impact on local groundwater. (Attachment A, p. 6.)

Attachment H, at Table III, estimates a total water demand of 14.00 acre-feet, with tasting room visitation at 0.74 acre-feet per year, and events and marketing at 0.42 acre-feet per year, for a combined total of 1.16 acre-feet per year. The estimates allow not a gallon of water for kitchen use for the tens of thousands of meals anticipated to be served annually.

5. The failure to provide notice to the Department of Drinking Water and the City of St. Helena has prevented full and complete review of the project as required by the CEQA.

State Clearing House records (SCH No. 2023030759) indicate that notice was not given to two relevant state agencies: The Division of Drinking Water and the City of St. Helena.

Accordingly, there has not been a full and complete review of the project as required by CEQA.

A. Division of Drinking Water

The proposed sole source of potable water has not been approved or reviewed by Department of Health or Division of Drinking Water. The 2005 Regulated Water System Memo warns planning staff:

There is a possibility that existing wells may not meet the construction requirements for a regulated water system. If the source does not meet the requirements, a new water supply will have to be developed, which must be reflected in the feasibility report. Prior to issuance of a building permit, the new water supply must be developed and full plans for the water system must be submitted and approved by this division.

Although in narrative the Applicant avows that there are no changes anticipated in the potable water system, a more detailed review reveals that the Division of Drinking Water (“DDW”) should have been given the opportunity to review the Application.

The Bartelt WAA states that the Duckhorn system is a NTNCWS (non-transient non- community water system). (Attachment H, p. 5) The Water Code provides that this is a regulated public water system.

Water quality standards are to protect the public health or welfare and to enhance the quality of water. DDW regulates public water systems; oversees water recycling projects; permits water treatment devices; supports and promotes water system security.

Duckhorn represents that the project is in compliance with Department of Health standards for a “non-transient non-community” water system, a classification is based upon the representation that Duckhorn employs less than 25 people. (Attachment H, p. 3.) It also represented “The approved number of 56 employees, which includes 45 full-time employees, five (5) part-time employees, and six (6) harvest/seasonal employees” (Attachment H, p.1) However, in response to a 2017 Napa County survey of employers, 228 people were reported to be employed.

Duckhorn is one of only three sites in the Napa Valley reporting arsenic exceedances, a situation that LSCE states is not attributable to groundwater conditions. (LSCE 2023, ES-9.) Contrary to representations that there are no reportable quantities of hazardous wastes on the property, Duckhorn filed substantial disclosures in 2012, and offers no explanation why similar quantities of similar hazardous materials are not present now.

While it is true that a domestic water well was approved, there is no evidence that the present well proposed to be the sole source of water is an approved public water system well. In fact, the evidence suggests a nomenclature shell game with public health. Careful attention is required.

Historically, Duckhorn operated under the trade name St. Helena Wine Company. Early operations were commenced at the same site, 3072 Silverado Highway, at the corner of Silverado Trial and Lodi Lane. Napa County Department of Public Health records show that in 1976 it approved one of two existing wells for potable water uses on the site:

Water Supply – Water will be supplied by two wells on the property. A bacteriological analysis of the older well located next to Silverado Trail was made in October of 1970 and was satisfactory. The newer well next to the river was installed under inspection by this office on June 18, 1975. This supply has not been analyzed for quality. The quantity of water from the wells is adequate.

In 1986, the original approved domestic well was destroyed. The new well drilled, and the sole source of water for the public water system (Attachment H, p. 22) is stated on its face to be an irrigation well. There is no record of approval of the current well for potable use. It is unknown whether it is capable of legally performing that task.

The Bartelt WAA (Attachment H, p. 5) directs the public to the drinking water Consumer Confidence Reports maintained by the Water Board. Review of those records reveals that Duckhorn filed no reports for three years, during the period of 2017 through 2019, and that the reports submitted in 2021 and 2022 are missing their mandatory certification. Not once in six years has a fully compliant report been filed (see Exhibit 1.)

There is no indication that DDW has been notified that the project’s entire potable water supply will be provided by one well, or that the well is potentially drawing from the Napa River aquitard. (Attachment D, p. 26); See Cal. Code of Regulations tit. 22 (Cal Regs), section 64413.1, subd. (3), which requires that special water treatment consideration be given to treat groundwater derived in part from a surface water source.) Furthermore, California Code of Regulations, section 64554, subdivision (c) provides that “Community water systems using only groundwater shall have a minimum of two approved sources before being granted an initial permit.”

For the foregoing reasons, it is submitted that the DDW must be given notice of the Application.

B. The City of St. Helena.

The City of St. Helena has not reviewed or commented on the project as occurred in the with the 1976 Use Permit. The Duckhorn project is within the vicinity of several recently approved projects that potentially impact a public trust interest. Any increase in the project’s water consumption may have an adverse impact on the City’s efforts to mitigate injuries to the public trust.

6. The MND does not include a necessary term of mitigation requested by CDFW.

The project proposes drilling horizontally under the Napa River to move water and wastewater from side to side of the property. (Attachment K – Horizontal Directional Drilling Exhibit.) While certain CDFW mitigation issues were included in the Mitigated Negative Declaration and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program (Attachment C – Mitigated Negative Declaration and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program), one critical matter was not. CDFW requested that a term of mitigation be included requiring a “frac out plan” to indicate the manner of protecting the Napa River from the mud slurry and lubricating fluids generated by drilled the horizontal conduits.

Correspondence from CDFW implies that such an agreement had been made.

Thank you for including a mitigation measure in the MND requiring the Project to submit an LSA notification for the directional drilling that would occur under the Napa River. Please include a frac-out plan with the LSA notification. CDFW, as a Responsible Agency under CEQA, will consider the CEQA document for the Project. CDFW may not execute the final LSA Agreement until it has complied with CEQA as a Responsible Agency. (Attachment O – Additional Public Comments, p. 5.)

While Chair Whitmer rather petulantly asserted that the CDFW requests for mitigation would be honored (see proceedings from Planning Commission May 3, 2023 Hearing.) CDFW was not included in Attachment B – Recommended Conditions of Approval and Final Agency Approval Memos, and its request for a frac plan is not in Attachment C – Mitigated Negative Declaration and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program.

It appears from correspondence with the Water Board that Duckhorn intends to argue that as the horizontal bore hole originates and terminates outside the boundaries of the Napa River a Fish and Game Code, section 1602 permit is not required. In that instance, absent an express requirement in the Mitigated Declaration, it is possible that the frac material will enter the river and environmental injury will certainly occur.

7. To the extent that Duckhorn seeks to process grapes from outside Napa County, the project does not comply with the terms of the Agricultural Land Preserve or the Williamson Act.

The Williamson Act (Government Code, section 51200 et seq.) enables Napa County to enter into contracts with private landowners for the purpose of restricting specific parcels to agricultural use. The primary intent of the program is to preserve agricultural land. In return for voluntarily restricting their land, landowners receive beneficial property tax assessments. The Williamson Act is designed to conserve the economic resources of the County by maximizing the amount of agricultural land preserved to maintain the local agricultural economy.

In 2017 Duckhorn expanded its Williamson Act contract by lot line adjustment to encompass the entirety of the project site.

Wineries are prima facie an acceptable land use in the Agricultural Land Preserve, but Duckhorn proposes to import grapes from another county to make up to 25% of its production.

In that respect the project is not an ancillary to Napa agriculture, and in fact this project diminishes the amount of farmed land in the County.

During the hearing, banter was conducted about saving fuel by not having to truck grapes out of county for processing. (see proceedings from Planning Commission May 3, 2023 Hearing.) No discussion was had regarding the anticipated fuel consumed by trucking into Napa grapes from outside the County. (Id.) Winery capacity that is surplus to local needs is of no use to Napa County agricultural interests and is therefore inconsistent with the Williamson Act.

8. Prior Use Permit agreements have obliged Duckhorn to provide a left-hand turn lane on Silverado Trail.

On July 24, 1980, the Napa Public Works Department wrote:

We stated in our May 28, 1976 letter to the Commission regarding, approved Use Permit #U-827576 that a left turn lane would be required at such time as the winery started public tours and tastings. The applicant as a condition of this application is to install a left turn lane on the Silverado Trail to channelize northbound traffic wishing to enter the facility.

On December 11, 1980, Napa Public Works wrote:

The applicant is to enter into a deferred improvement agreement with the county to install a left turn storage lane on the Silverado Trail to channelize North bound traffic wishing to enter the facility, at such time as public tours and tasting are offered.

On November 26, 1982, Daniel J. Duckhorn wrote:

I refer you to the last paragraph of the December 11, 1980 letter to Planning from your Department. The requirement’ specifically states that such left turn lane will be installed at such time as public tours and tastings are offered.

Conclusion

We manage what we measure.

For the foregoing reasons, Water Audit respectfully prays that the decision adopting the Mitigated Negative Declaration and Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Program and approval of Use Permit Major Modification Application P19-00097-MOD be reversed and that Duckhorn be instructed to prepare an Environmental Impact Report if it should choose to proceed with the proposed project.

Respectfully,

William McKinnon General Counsel

Water Audit California

___

1 From Table 2A from the Napa County Water Availability (WAA – 2015) – Design, Construction and Guidance Document.

2 Substantial evidence in support of present environmental injury was not considered. See following.

3 GSAs are charged with procedural and substantive obligations designed to balance the needs of the various stakeholders in groundwater in an effort to preserve, and replenish to the extent possible, this diminishing and critical resource. (Water Code, sections 10721, subds. (u), (v), (x)(6), 10723.2, 10725.2, 10725.4, 10726.2, 10726.4, 10726.5.)

4 Without making allowance for the removal of nearly 25% of groundwater recharge on land impaired by buildings and parking.